Almost 1 in 5 Utah students are Hispanic, but Utah school boards lack Latino voices

Diego Joaquin Florez and Fernando Mendiola-Gacia take their food as students at Granite District’s James E. Moss Elementary School eat their breakfast in their classroom after school has started for the day on March 18, 2016. Almost 1 in 5, or 19%, of Utah public school students are Hispanic. (Scott G Winterton, Deseret News)

Estimated read time: 11-12 minutes

SALT LAKE CITY — Arlene Anderson grew up in a family where education was a top priority.

Her parents, both Mexican immigrants, understood the value of education even though neither attended school beyond about third grade. Despite their emphasis on education, their limited English and literacy skills meant they often couldn’t fully participate in their nine daughters’ education.

“My father, who was limited English proficient, and my mom would go to parent-teacher conferences and they just wanted to make sure as long as the teacher was nodding, saying ‘Yes, everything’s great’ — that’s all that was important to them because they knew that education was going to help their daughters,” Anderson said.

Now, as the first Hispanic member of the Ogden City School Board, Anderson is the person she wishes her family had growing up.

“I wish my mom and dad had somebody like me on the school board, or even a teacher, that could speak to them in their own language to let them know how their child is doing,” Anderson said. “They didn’t have that, but I’m hoping to bring that.”

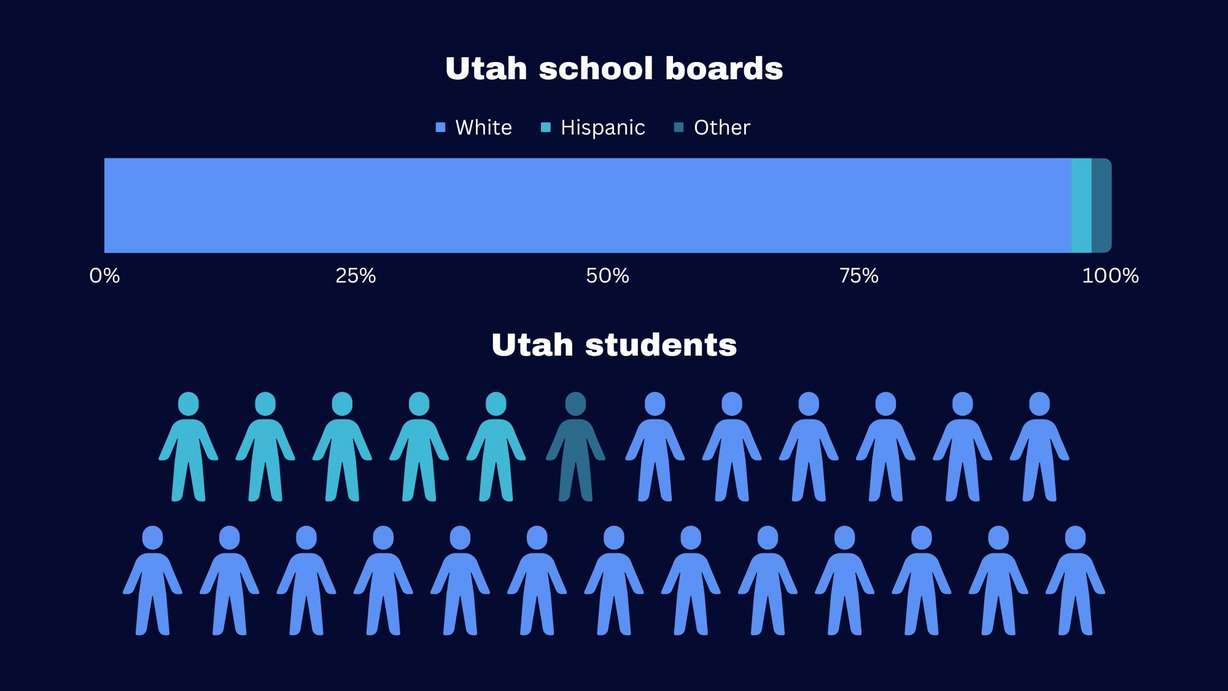

That type of representation is rare in Utah school boards, however. There appear to be only four Hispanic school board members in the entire state: Anderson, Stacy Bateman of Alpine, Nate Salazar of Salt Lake, and Ryan Despain of Tintic.

That’s despite the fact that almost 1 in 5, or 19%, of Utah public school students are Hispanic.

Hispanic students also make up the largest minority group in all but two districts — Ogden, where they are the majority at 50%, and the San Juan District, where 54% of students are American Indian or Alaska Native. Those two districts, along with Granite and Salt Lake, have non-white majority student populations.

Utah isn’t alone in its lack of representation. A national EdWeek Research Center survey of over 1,500 school board members found that 86% of respondents said they had no Latino colleagues on their board.

Charting the racial and ethnic makeup of Utah’s school boards

KSL.com asked all 41 school districts in the state whether they have any members of color on their school boards, and specifically whether any members are Latino or Hispanic.

Twenty-eight districts answered that request, 10 declined to answer and three did not respond. KSL.com also reached out to the Utah School Boards Association to ascertain how many people of color are serving on school boards across the state and was told the association does not track that information.

The districts that declined to answer — Canyons, Davis, Duchesne, Granite, Nebo, North Sanpete, Park City, South Summit, Uintah and Washington — largely said they did not have information about school board members’ race and ethnicity and punted the request, inviting KSL.com to ask school board members directly about their race and ethnicity. KSL.com was able to gather some responses from board members but most did not respond.

“To be clear, board members are elected by the general public and as elected officials, we do not collect their ethnic/nationality information. And I would be embarrassed to assume what they identify as in terms of their ethnicity,” said Granite School District spokesman Benjamin Horsley in an email. “Additionally, it would be protected/private information from the file under state statute and I am not comfortable asking our board members for this information.”

The Granite School Board issued a statement in response to KSL.com but did not answer questions about the racial and ethnic makeup of the board.

“We don’t ask board members their ethnicity, medical histories, sexual orientation, or disabilities; rather, we encourage all board members to look out for all students, families and employees of Granite,” the statement reads.

Davis School District referenced a Utah state law about records requests that didn’t pertain to KSL’s request as the reason why it was unable to disclose whether it has any school board members of color.

Ruben Archuleta, chairman of the National Hispanic Council of School Board Members, said school boards that choose to ignore race and ethnicity in their approach are not effectively serving diverse student populations.

“I don’t think it’s effective at all,” Archuleta said. “Latino students are the second largest demographic in the Utah schools, so that’s a concern.”

The case for more Hispanic representation

Studies on the impact of minority representation on California school boards, for example, found that increased representation is linked to improved academic performance and greater financial investments in schools.

“I think the takeaway here is that one member seems to make a difference,” said Brett Fischer, the author of one of the studies and researcher the University of California, Berkeley, told Education Weekly. “Diversity of viewpoints on the board matters and listening to the board matters. The role of the school board’s individual members is not trivial.”

Utah’s Latino school board members also described how their lived experiences have impacted their approaches to serving on school boards. Many of them stressed that they’re able to bring perspectives that might not otherwise be considered on the board.

Anderson, for example, delivered a bilingual commencement speech at Ben Lomond High School and helped push for a diversity and equity council made up of community members and district officials to examine policies and procedures. Despain, who serves in one of the state’s smallest districts, subs for the high school’s Spanish program. Salazar proposed a resolution denouncing family separation practices at the border and affirming the board’s commitment to protecting immigrant families.

“Representation does matter,” Anderson said. “It’s not just because of what I look like but also understanding the culture and even being able to speak the language, the nuances that come, and having similar experiences — that’s what matters.”

Salazar said his experiences, such as being the only Hispanic student in some of his elementary school classes, help him bring a different viewpoint to the board. He also said growing up with representation by the late Latino community leaders Archie Archuleta and Sen. Pete Suazo helped give him the confidence to run for office.

“I don’t think that it’s necessarily on purpose that issues of equity don’t rise to the level of significance in certain communities or in certain elected boards or what have you,” he said. “I think it’s powerful when we’re talking about these types of topics or issues, to say, ‘Hey, I know what that feels like. I know what it’s like to be in the minority or in the ‘other’ category, and this is why we need to shake up how we do business and why we need to make the decisions that we need to make and push for the initiatives that we need to push for to create that equity and that balance in our schools and in our city.”

For Bateman, seeing how her family members who immigrated from Mexico had to assimilate in the U.S. has made her acutely aware of ways institutions can sometimes fall short when working with people of different backgrounds.

“I understand the weight of what I am doing and what the women before me did so that they could have a voice and a vote,” she said. “That whole time during election season, I just kept thinking: I wish they were here to see that we encourage the languages that our families have in this district, and that we want to send communications home in Spanish, and we want to make sure that the parents understand what’s going on instead of them trying to fit what they think we want them to be.”

As a school board member, she said she works hard to identify cultural, linguistic and socioeconomic barriers and make sure they’re considered during policy discussions.

“I think sometimes people in leadership positions make grossest assumptions that aren’t even accurate a little bit, but it’s based off their experience,” Bateman said. “Sometimes the narrative becomes the school is telling parents what they’re going to do. I don’t think people do that maliciously; I think it’s just we don’t always understand how different cultures work or who a leader is within that particular group.”

Student data is for 2021-2022 from the Utah State Board of Education. School board data is based on estimates from a KSL.com survey of Utah’s 41 school districts. (Photo: Sydnee Gonzalez, KSL.com)

Student data is for 2021-2022 from the Utah State Board of Education. School board data is based on estimates from a KSL.com survey of Utah’s 41 school districts. (Photo: Sydnee Gonzalez, KSL.com)

Diverse representation can also go beyond just race and ethnicity. Despain, for instance, dropped out of high school for a period, served in the army, and started his own business. He said those experiences have allowed him to push for trades as a legitimate path for students who may not be interested in college.

“The importance of representation — it doesn’t have to be a Latin person, but having anybody who has grown up in a dual language home or has been at least abroad a few times — it just helps with more understanding,” Despain said. “Not saying that anybody that hasn’t doesn’t have that understanding, but it does open your eyes a little bit to the situations from those people that might be coming in.”

Why aren’t there more Hispanic and Latino candidates for school board?

As with any elected position, running for school board requires time, money and connections — resources that have historically been less accessible to marginalized communities. That’s compounded by the fact that Utah Latinos have a lower voter turnout.

It’s a reality that Granite School Board candidate Yvette Romero, a social worker and University of Utah professor, is seeing firsthand.

“There’s so many things that, when it comes to resources and community investment in our community, that really create barriers for us to just jump into things like this,” she said. “I’m finding every opportunity to try to engage with as many people as possible, and it’s really hard.”

“This is meaningful representation,” she added. “I think that the opportunity is perfect to bring in somebody who is from the neighborhood, who is bilingual, who is bicultural, who has lived with many of the similar things that kids in the neighborhood and families here have lived, and who has a willingness to invest in those relationships because we need them. We need them present.”

The four current school board members faced a range of political landscapes when they chose to run. Some challenged incumbents; others ran unopposed. For some, it was their first experience running a campaign.

Salazar, of Salt Lake, lost two campaigns prior to being elected to the school board. He described feeling a sense of imposter syndrome when deciding whether to run.

“I think that there’s a valid point that if people don’t run, then there won’t be representation — and even just running it says a lot. Even if you’re not successful, it’s a marker of ‘Yes, I can do that. Yes, I can participate.'” he said. “I think the more and more folks and people of color that do run for office, the more that it sets that tone that this is something we’re capable of doing.”

Running for the Ogden School Board was Anderson’s first campaign. She called it “an uphill battle” since her opponent was the school board president and had been there for almost two decades.

“I had helped with campaigns, but I did not realize how hard it was — and that may be a factor as to why people of color may not run,” she said, adding that those support networks sometimes fade after the election season. “I think even once you get on that board — for me, with my experience — it is very lonely. And I had to remind my supporters, you helped me get here; you have to continue to help me work through this.”

Despain ran unopposed for a seat on Tintic’s school board after friends in the district encouraged him to run. He said he’s surprised there aren’t more Hispanic school board members but understands why.

“It’s a different thing. I didn’t think about running at first,” he said, adding that working from home because of the COVID-19 pandemic made it easier to volunteer.

“The Hispanic community is very family oriented,” he added. “They help each other out, they’re always volunteering, they’re always doing something and staying busy in their communities — but mainly with their families. So for them to push and want to be on a school board, maybe it’s just not something that they’re looking into or needing. I think school boards do really well, anyway, with trying to be very diverse here in Utah.”

What’s the solution to get more Latinos involved in local political races like school boards?

Romero and Salazar said current elected officials should help mentor and support up-and-coming leaders and encourage them to run. That can include making school community councils and other meetings more accessible, such as holding a meeting during lunchtime when more parents can attend and personally inviting groups who are underrepresented.

“My hope is that I do plant the seed for our future leaders,” Anderson said. “That if they can see me at the school-board level, then I hope one day they can see themselves as a school board member.”

×

Photos

Most recent Voces de Utah stories

Sydnee Gonzalez is a multicultural reporter for KSL.com covering the diversity of Utah’s people and communities. Se habla español. You can find Sydnee at @sydnee_gonzalez on Twitter.

Comments are closed.