Polis moves to revamp team dealing with Colorado River drought crisis | news

Under pressure to protect the state’s dwindling supply of Colorado River water from other states with more political clout, Colorado is reshuffling its river leadership team and asking lawmakers to approve $1.9 million in funding for a new policy and technology task force on river issues.

The changes include shifting Rebecca Mitchell from her role as director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board to the executive office at the Colorado Department of Natural Resources.

There she will focus on her work as Colorado’s commissioner on the Upper Colorado River Commission, according to a letter from Dan Gibbs, executive director of the Colorado Department of Natural Resources.

gov. Jared Polis’ proposal, contingent on lawmakers’ approval, also calls for adding more than a dozen new positions to the Colorado Water Conservation Board and the Colorado Department of Natural Resources and adding $5 million to fund state water plan grants. If approved the changes would take effect July 1 when the new state budget takes effect, according to Chris Arend, Department of Natural Resources. spokesman.

Mitchell was appointed to the Upper Colorado River Commission by Polis in 2019 and has maintained a dual role as Colorado Water Conservation Board director and commissioner on the commission.

In a statement, Arend said the changes are critical to ensuring the state can adequately protect its share of the drought-stressed river.

“The Colorado River system is facing many challenges due to a dwindling water supply, which are amplified by one of the worst droughts in recorded history,” Arend said.

“These issues are exacerbated by increasing tension in interstate negotiations that are contributing to unprecedented pressure on Colorado’s water supplies.”

Lee Miller, a water attorney who represents the Pueblo-based Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District and who has been part of a group of experts advising Mitchell on Colorado River issues, said there needs to be clarity around who reports to whom and what the relationship between the Colorado Water Conservation Board and the new policy and technology team will look like. When a replacement for Mitchell would be named is unclear.

“It’s important that everyone know that we have a consistent leadership voice,” Miller said. “So if staff is responding to two different leaders or if we are not completely organized, that initially is going to be problematic.

“I’m not suggesting it’s going to be a problem. I just don’t know. We can’t afford to have organizational confusion because we really are getting down to the important stages of the negotiations,” he said.

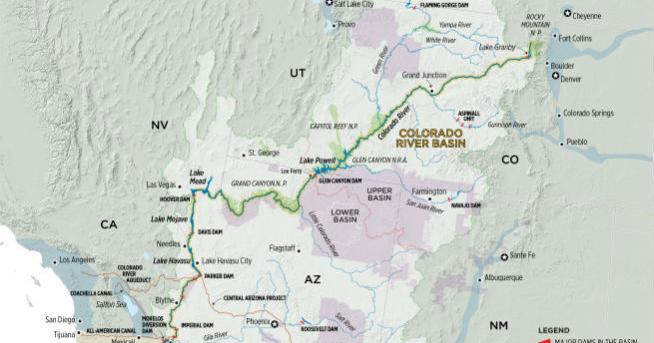

Now 22 years into a megadrought widely believed to be the worst in 1,200 years, the highly developed river system is on the brink of collapse, with lakes Powell and Mead falling dangerously close to dead pool, a water level so low that, if it is reached, Powell won’t be able to produce hydropower and Mead won’t be able to serve the millions of people in the Lower Basin who rely on the river.

The river begins in Colorado’s Never Summer Mountains, high in Rocky Mountain National Park. It gathers water from major tributaries in Colorado, such as the Yampa and Gunnison rivers, and throughout the Upper Basin, accumulating 90% of the stream flow that it will provide throughout the seven-state river system — thanks to the runoff from the Upper Basin’s deep mountain snows.

But since 2002, those mountain snowpacks have been shrinking, crushed by higher temperatures and fewer snow days.

Beginning in July 2021, and again this year, the US Department of the Interior ordered, for the first time, emergency releases from Utah’s Flaming Gorge, Colorado’s Blue Mesa and New Mexico’s Navajo reservoirs. But that has done little to restore levels, although the releases are credited with providing some protection to the power supply.

With the crisis deepening, in June US Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Touton ordered the seven states to find ways to cut water use by 2 million to 4 million acre-feet of water by 2023.

While Lower Basin states have been forced to begin cutting back water use under a special set of operating guidelines and drought plans approved respectively in 2007 and 2019, negotiations in recent months have failed to achieve the federally ordered cutbacks.

At the same time, the drought has continued, and this winter is forecast to be dry once again. In response, last week, the federal government announced it would expedite negotiations on a new set of operating guidelines designed to protect Lakes Powell and Mead to help restore the river.

Under the terms of the Colorado River Compact of 1922, the river’s supplies are divided equally between the Upper and Lower basins. But because the Upper Basin states have smaller and fewer reservoirs than the Lower Basin, users here have had to cut back their water use as the drought has continued. At the same time, Lower Basin users have been able to rely on stored supplies in Powell and Mead; at least, until now. The crisis has left Colorado water users nervous that the state hasn’t moved quickly enough to protect itself from potential new demands for more water from the Lower Basin states.Larry Clever manages the Ute Water Conservancy District, which serves Grand Junction, among others, and which has fairly senior rights to Colorado River water.

He has been concerned about what he describes as the state’s failure to be more aggressive in demanding changes in the Lower Basin, including major cutbacks in water use. He said the state’s new approach could be a good thing.

“We’ve got to get our butts in gear and do something,” Clever said. “Will this result in that? I hope so. In my opinion, we’re in trouble.”

Jerd Smith is editor of Fresh Water News; 720-398-6474; at [email protected]; @jerd_smith.

Comments are closed.