As the 2022 water year comes to a close, how did Utah fare?

SALT LAKE CITY — Laura Haskell finds it difficult to describe the 2022 water year because it has been all over the place.

The water year, which began in October 2021, started out very strong, leaving Utah’s snowpack — the amount of water held in the snow that falls in the state’s mountains — well above average heading into the actual 2022 calendar year.

That well of water essentially shut off after the first week of the calendar year, though. Utah posted its third-driest January on record and the start of February wasn’t great, either. Some wintry spring storms did help water levels for the northern half of Utah; however, Utah’s final 2022 snowpack ended up about 75% of normal, not enough to fully recharge the state’s struggling reservoirs.

A mostly normal monsoon season helped precipitation totals, especially in the southern and central parts of the state, but those numbers didn’t impact Utah’s reservoirs much. The record heat in between the monsoonal events also hurt totals.

Add it all up, and it wasn’t a terrible water year, but it also wasn’t a great one.

“Coming on the heels of the drought years, it didn’t really make the situation a lot better,” said Haskell, the drought coordinator for the Utah Division of Water Resources. “There was a little bit of good, some bad, and it kind of all meshed together to be kind of meh.”

Localized precipitation totals

The final statewide figure is still being calculated, but Utah ended August with an average of 10.73 inches, putting the state on pace for its 34th driest water year since 1895. The 30-year normal is 13.46 inches, according to National Centers for Environmental Information data.

Coming on the heels of the drought years, (the 2022 water year) didn’t really make the situation a lot better. There was a little bit of good, some bad, and it kind of all meshed together to be kind of meh. —Haskell, Utah Division of Water Resources

Available National Weather Service data offers a better window into the final water year’s precipitation totals. Salt Lake City, for instance, enters the final day of the water year having collected 13.14 inches of precipitation over the past 12 months, 2.34 inches below the 30-year normal of 15.48 inches.

Barring final day precipitation, it will be the 41st driest water year on record for the city since 1874, per weather service records. However, it’s an improvement from the 2020 and 2021 water years that produced 9.18 and 10.46 inches of water, respectively.

Some locations exceeded the normal, especially because of the strong start to the water year. The KVNU site in Logan has calculated 18.38 inches of precipitation, which is 1.78 inches above the listed normal from 1991 to 2020. Its figures were bolstered by a strong October, which produced 4.79 inches of precipitation, a little more than a quarter of its water year total.

Here are some other local totals entering the last day of the water year, per weather service data:

- Cedar City: 9.24 inches, 1.78 inches below the 30-year water year normal

- Moab: 9.27 inches, 0.14 inches above the 29-year calendar normal

- Provo (BYU campus): 14.23 inches, 1.61 inches below the 21-year calendar normal

- Randolph: 13.06 inches, 1.3 inches below the 29-year calendar normal

- tools: 15.21 inches, 2.12 inches below the 21-year calendar normal

Drought and reservoirs

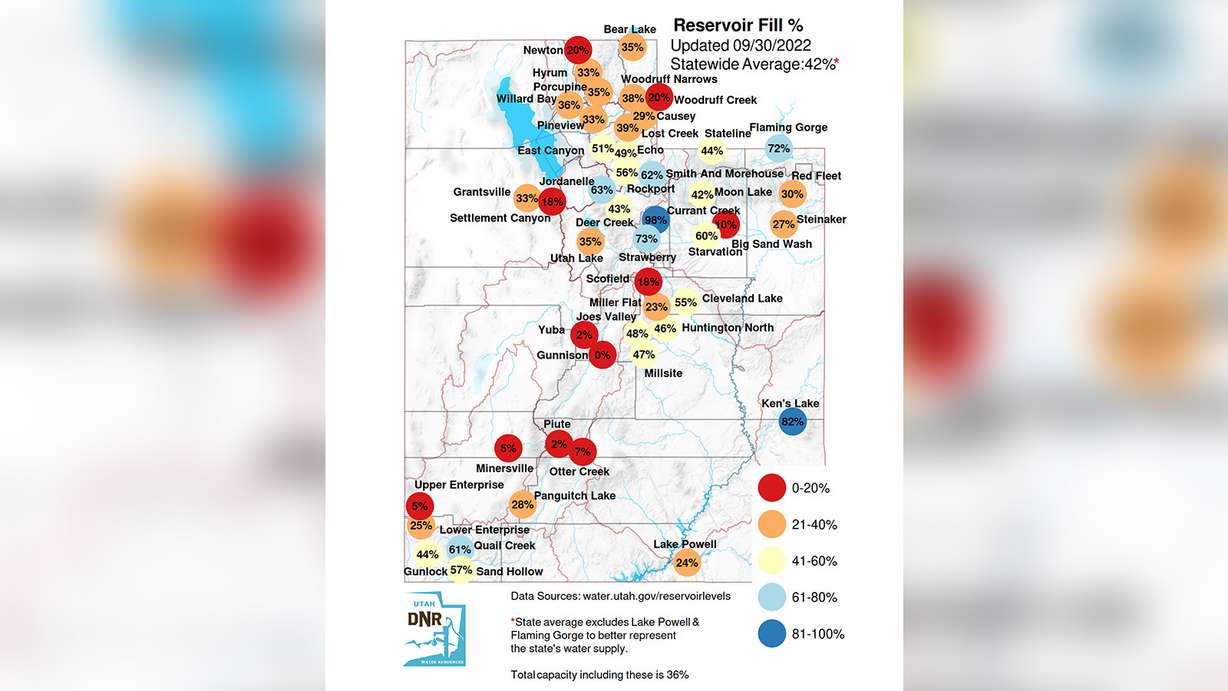

Meanwhile, Utah’s vast reservoir system will end the 2022 water year at 42% of capacity, per Utah Division of Water Resources data. This figure includes all the reservoirs in Utah aside from Flaming Gorge (72% of capacity) and Lake Powell (24% of capacity) because excluding those two better represents the state’s actual water supply, officials say. Utah’s water capacity is at 36% if including the two reservoirs.

Utah’s reservoirs are down about 5 percentage points from the end of the 2021 water year, so the system is basically back to where it started this time last year. However, Haskell views this as a bit of a victory given the below-normal snowpack collection in the winter.

“People used less (water) on their landscapes and people really conserved,” she said. “To not have the reservoirs any lower than they were last year after only getting 75% of our (normal) snowpack, that’s good news.”

This map shows water levels at Utah’s largest reservoirs as of Friday, the last day of the 2022 water year. (Photo: Utah Division of Water Resources)

This map shows water levels at Utah’s largest reservoirs as of Friday, the last day of the 2022 water year. (Photo: Utah Division of Water Resources)

State water regulators released a report in August that found “billions” of gallons were conserved again this summer, as Utahns cut back on water use. Salt Lake City Public Utilities officials reported last week that they were able to reduce water consumption by 2.9 billion gallons, as the state continues to reel from the drought.

Utah wasn’t able to escape its current drought this water year, but the better total precipitation did ease the severity a bit.

This ends the 2022 water year with 56% of the state experiencing at least extreme drought conditions, including nearly 4% in exceptional drought, according to the US Drought Monitor. The organization listed 70% of Utah in at least extreme drought this time last year, including one-fifth of the state in exceptional drought.

All eyes on ’23

The focus now shifts to the start of the next snowpack season, which typically begins in October and continues through the first half of the 2023 water year. The natural snowpack collection and runoff system accounts for about 95% of Utah’s water supply.

The second piece of good news is that Utah’s soil moisture levels are “a little bit above average” heading into the next water year, according to Haskell.

This is vital because moist soils allow for a more efficient snowpack runoff, and that’s what fills up the reservoirs. In spring 2021, researchers found that most of the snowmelt went into the ground because soil moisture levels were extremely dry at the end of 2020. This spring, the biggest issue was that there wasn’t enough snow to melt into the reservoir.

The hope is that soil moisture levels will remain “fairly high” in the next few weeks so that the next snowpack will make it to the state’s reservoirs and streams, Haskell said.

Rob Steiner clears snow from a bench at Snowbird on Oct. 12, 2021.

Rob Steiner clears snow from a bench at Snowbird on Oct. 12, 2021.

There is also growing optimism for the snowpack collection itself. The National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center expects La Nina conditions to continue into the winter, the third consecutive time that’s been the case. Historically, a third-straight La Nina winter has meant dry conditions in Utah, and the center’s long-range forecast originally called for as much.

However, the center on Sept. 15 updated its outlook for the first three months of the new water year to list the northern half of the state in “equal chances,” meaning there is no indication for an above normal, below normal or normal precipitation total for the duration of October, November and December. Southern Utah remains listed with odds leaning toward a dry start to the water year.

“Any upgrade in that forecast is certainly welcomed because we’d prefer to not have a very hot and very dry next three months,” she said.

Whatever the case may be for the 2023 water year, it’s likely not going to be the year that solves the drought. Experts say, as a rule of thumb, it takes about as many years to exit a drought as it takes to enter it. Utah’s current drought started back in the spring of 2020, though the state is also in the middle of the West’s two-decade-long megadrought.

That means this winter’s snow collection — good, bad or ugly — likely won’t change the way water conservation is promoted in the state. It could take years to recover what has been lost in the drought if it happens at all.

“Our hope is that people are making permanent changes, changing the way they water their lawns and realizing that, perhaps, we’ve been overwatering, she said. “We’re hoping that people are understanding (that we need) better landscapes for where we live.”

Comments are closed.