How Utah boarding schools stripped Native students of their culture

Uintah School: ‘Even the smallest girls’ put to work

Location: White Rocks, Utah

Years open: 1874 to 1952

Bands of the Ute Tribe roamed a wide region that included what is today Utah and Colorado. By the early 1870s, the Uintah Band had been pushed onto its reservation in the Uinta Basin, about 150 miles east of Salt Lake City.

In an 1874 report to the US Department of Interior, federal agent John J. Critchlow said he was eager to open a “boarding manual-labor school” for Ute children.

His first version — a day school he and his wife taught out of their home — faltered, opening and closing for a lack of funds and interest from Ute parents. Critchlow wrote to the department complaining that he must keep the children “from the demoralizing influences in their lodges.

”He won support after a visit to Washington DC and in January 1881, the Uintah Boarding School opened — the first Indian boarding school in Utah, launched just two years after the infamous Carlisle Indian Industrial School started in Pennsylvania.

The Presbyterian Board of Missions held the initial contract to run the school, according to Critchlow’s annual report, and it initially had 13 students. But after two months, none remained. The Presbyterians withdrew their support.

Ute students standing in a line outside Uintah Boarding School at Whiterocks, undated. Used by permission of Uintah County Library Regional History Center, all rights reserved.

“The Indians made many excuses for not sending their children to school,” Critchlow wrote. “They were ignorant and superstitious and feared that harm might come to their boys and girls.”

The harms the students endured at the school were ignored, or unrecognized, and downplayed by Critchlow and the early federal agents and superintendents who followed him.

Aiming to sever the children from their culture, the school cut their traditional long hair, required them to wear uniform clothing, forbid them to speak their language, taught a rigid academic curriculum foreign to them and pressed them into manual labor for hours a day. In racist language, year after year, federal agents dismissed the traditions and concerns of Ute parents, even when students died.

The Department of Interior formally took over school operations in 1883, and the federal government ran the Uintah Boarding School for the next seven decades.

In that first year, as 17 students attended, the teacher wrote that the “Indian pupils are not as bright as white children.” The boys cut wood and did gardening. The girls did sewing, washing and cooking. A later report notes: “Even the smallest girls were required to do such work as they could perform in the various departments.”

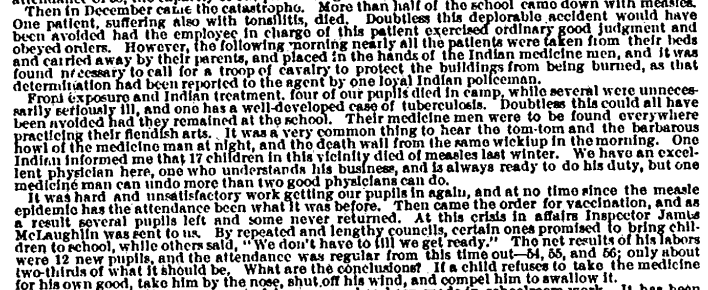

In his 1901 report, Uintah School Superintendent EO Hughes described the measles outbreak in the previous year.

In his 1901 report, Uintah School Superintendent EO Hughes described the measles outbreak in the previous year.

Image transcript:

Then in December came the catastrophic. More than half of the school came down with measles. One patient, suffering with tonsillitis, died. Doubtless this deplorable accident would have been avoided had the employee in charge of this patient exercised ordinary good judgment and obeyed orders. However, the following morning nearly all the patients were taken from their beds and carried away by their parents, and placed in the hands of Indian medicine men, and it was found necessary to call for a troop of calvary to protect the buildings from being burned , as that determination had been reported to the agent by one loyal Indian policeman.

From exposure and Indian treatment, four of our pupils died in camp, while several were unnecessarily seriously ill, and one has a well-developed case of tuberculosis. Doubtless this could all have been avoided had they remained at the school. Their medicine men were to be found everywhere practicing their fiendish arts. It was a very common thing to hear the tom-tom and the barbarous howl of the medicine man at night, and the death wail from the same wickiup in the morning. One Indian informed me that 17 children in this vicinity died of measles last winter. We have an excellent physician here, one who understands his business, and is always ready to do his duty, but one medicine man can undo more than two good physicians can do.

It was hard and unsatisfactory work getting our pupils in again, and at no time since the measles epidemic has the attendance been what it was before. Then came the order for vaccination, and as a result several pupils left and some never returned. At this crisis in affairs Inspector James MvLaughlin was sent to us. By repeated and lengthy councils, certain ones promised to bring children to school while others said, “We don’t have to till we get ready.” The net results of his labors were 12 new pupils, and the attendance was regular from this time out—54, 55, 56; only about two-thirds of what it should be. What are the conclusions? If a child refuses to take the medicine for his own good, take him by the nose, shut his wind, and compel him to swallow it.

Such labor by Indigenous children — for decades, across the country — benefited the schools more than the children, the influential Meriam report pointed out in 1928.

The official Course of Study for Indian Schools, the report noted, conceded that boarding schools “could not possibly be maintained on the amounts appropriated by Congress … were it not for the fact that students [i.e., children] are required to do the washing, ironing, baking, cooking, sewing; to care for the dairy, farm, garden, grounds, buildings, etc. — an amount of labor that has in the aggregate a very appreciable monetary value.”

In early years in the Uinta Basin, some Ute parents refused to send their children unless they were paid for their work. The government responded to them, and to other parents who refused to have their children attend, by no longer providing rations to those families, according to a superintendent’s report. Soldiers were also called to forcibly enroll students. Some Utes hid out in the mountains to avoid that; others tried to fight back.

In 1884, Critchlow proposed sending all of the children to Eastern schools to cut them off further from their families. Some were transferred to Carlisle or to a school in Grand Junction, Colo.

By 1896, there were 66 Ute children attending the Uintah Boarding School, and that is the first year that the federal reports note a death. One girl, the superintendent wrote, “died with consumption,” which likely meant tuberculosis.

There is no official total of how many children died at the school or at any Indigenous boarding school in the country. But according to annual Interior reports available up until 1930 (still 22 years short of when the school closed), at least 33 deaths were reported at the Uintah Boarding School between 1896 and 1904.

In one year — 1901 — 17 of the 65 students were reported to have died of measles. It’s possible there were more deaths, overall, at the school or related to attendance there.

Forrest Cuch, a former education director for the Ute Tribe, believes some of the students who died were buried on the school grounds.

Cuch’s mother, Josephine LaRose Cuch, attended the school for a few years, starting when she was 6 or 7 years old in the 1920s.

“The harshness that they experienced, that I know of what was being forbidden to speak the Ute language. That was quite painful and traumatic to them,” Cuch said.

Children were also not allowed to practice their traditions — such as the Bear Dance — or wear traditional clothes, Cuch said, and they were forced at times to attend an adjoining Episcopal Church (the faith, though, did not sponsor the school).

The school later hired some Ute staff members, and they were expected to enforce its policies. Cuch’s great-aunt, Ethel Grant, came to regret her employment there, Cuch said, and worked to restore the language among the tribe’s kids.

“She was really heartbroken about that, that at one point in her life she was an oppressor or colonializer,” he said.

Boys at Uintah Boarding School at Whiterocks, undated. Used by permission of Uintah County Library Regional History Center, all rights reserved.

Boys at Uintah Boarding School at Whiterocks, undated. Used by permission of Uintah County Library Regional History Center, all rights reserved.

After the Randlett boarding school built for the Uncompahgre band closed in 1905, its students transferred to Uintah Boarding School. The Whiterocks school hit its enrollment peak in the 1920s and 1930s; by 1927, the school had expanded from elementary grades to includes classes up to eighth grade.

In 1931, The Roosevelt Standard reported that 125 students were attending, with about half of them also boarding there.

The school closed on June 30, 1952, as the federal government promoted the transfer of Native American students into public school systems, according to Fred Conetah, the Ute author of “A History of the Northern Ute People.” A fire destroyed the remaining buildings in 1974.

In the public school system, Cuch charges, Indigenous students were neglected and left to fail. In the 1970s, the dropout rate for the Ute Tribe’s students hit 90%, he said.

Test scores for Indigenous students in Uintah School District today remain significantly behind their white peers in most subjects. “The picture hasn’t changed much,” Cuch said.

Today, the Ute tribe has more than 3,000 members, with about half living on the Uintah and Ouray Reservation. It operates its own charter school, Uintah River Charter High School, for students who are falling through the cracks — a gap Cuch sees as part of the legacy of boarding schools.

Comments are closed.