How would you draw the Utah election cards? This is how these residents drew theirs

Voters cast their ballots in Trolley Square in Salt Lake City on November 3, 2020. With the 2020 census data available, Utah is in the process of creating new electoral district maps for the next 10 years. (Scott G. Winterton, Deseret News)

TAYLORSVILLE – When it comes to putting representative boundaries together, Stuart Hepworth sees the streets as a key component that brings the different boroughs together.

For him it is important that someone can drive from one constituency in Utah to another without accidentally driving to another district. This can be difficult in the Beehive State.

“Utah’s geography is quite difficult for someone who values cohesion and proximity to the road. Compared to other states, it is much more difficult to create compact counties that are contiguous,” he said during a meeting of the Utah Independent Redistricting Commission Tuesday evening. “With Utah’s geography, you have areas that look like they should be connected on a map, such as counties of Uintah and Grand, where there is no real way to get between them.”

As the Utah Independent Redistribution Commission continues to gather feedback on the state’s new voting cards for the next decade, its leadership spent most of its 2½-hour Tuesday session listening to a handful of state residents discuss their own Congressional, legislative and legislative meetings Have designed school blackboards.

A custom card creation feature launched last month is one of the Utah Independent Redistricting Commission’s innovative ways to gather public feedback in order to develop fairer voting cards that will be honored by Utah lawmakers later this year.

The Commission has received a modest response over the past few weeks. Commission officials said they received more than a dozen congressional card submissions, but they struggled with school authorities and were only given two in that category.

The system allows anyone to design cards and submit them to the committee. It attracted people like Hepworth, a native of South Jordan and a current student at the University of Utah. Hepworth was perhaps the star of Tuesday’s meeting, showing off not only his drafts for all four voting cards but also several congressional district options based on different definitions of the task.

Explaining his map of the Utah House of Representatives to the commission, he said that in addition to his street theory, he wanted to pay more attention to neighborhoods and similar communities – a term referred to as interest groups – rather than leaving cities in the same counties.

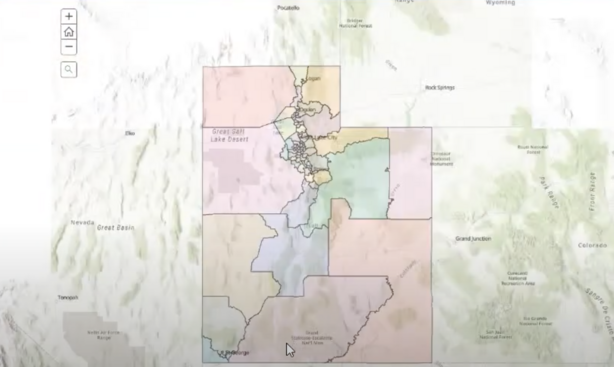

A design by the Utah House of Representatives submitted by Stuart Hepworth. The University of Utah student said he was trying to make sure each district is designed so that someone can drive from one Utah constituency to another without accidentally getting to a different district. (Photo: Utah Independent Redistricting Commission)

A design by the Utah House of Representatives submitted by Stuart Hepworth. The University of Utah student said he was trying to make sure each district is designed so that someone can drive from one Utah constituency to another without accidentally getting to a different district. (Photo: Utah Independent Redistricting Commission)

“I tried to avoid dividing neighborhoods into cities with very well established neighborhoods,” he said. “One of the (big) things in all of my maps is that the roads are connected so you can travel from one district to another without going to another district.”

Interest groups are an important part of redistribution. They are neighborhoods and communities with common interests. So if you want to be in the same constituency as your neighbor, that’s a community of interests. The same can be true of a specific neighborhood in a city, such as Glendale in Salt Lake City or East Bay in Provo.

What is not an interest group? Trying to keep a county in the same district is part of the feedback the commission has received, according to Joey Fica, a GIS and logistics specialist with the Utah Independent Redistricting Commission.

The Commission allows residents who may not be designing maps to indicate on the map the community of interest they wish to receive. The Commission sees economic, educational, environmental, ethnic, industrial, linguistic, local government, neighborhood and religious communities as examples of interest groups.

These comments can be viewed online by anyone. For example, a resident of the Sugar House neighborhood of Salt Lake City said he saw “traffic, air pollution, or safety concerns” as a unifying issue for his area, a reason he wanted to be in the same boroughs. A resident of Vernal wrote that it was important to hold the Native American land and reservations in eastern Utah together so that they can “maintain culture and … rights.”

Provo-resident Daniel Friend argues that rural Utah is possibly the state’s largest community of interests. For this reason, he designed a congressional map with one huge district for rural parishes and three smaller districts dividing the Wasatch Front population cluster.

“Though it’s very sprawling geographically, rural Utah has so many things in common,” he said. “One thing that came up in the census is that many rural Utah areas are losing population, many of the Wasatch Front are gaining. I don’t know how one (agent) can represent these two interests because they are direct opposites. “

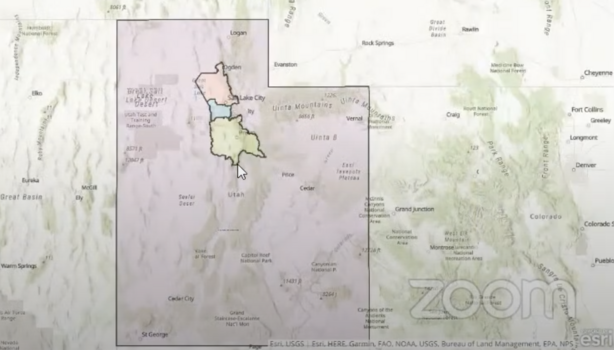

A Draft by Congress in Utah submitted by Daniel Friend, a Provo resident. He said his design was inspired by connecting rural Utah with a unifying district. (Photo: Utah Independent Redistricting Commission)

A Draft by Congress in Utah submitted by Daniel Friend, a Provo resident. He said his design was inspired by connecting rural Utah with a unifying district. (Photo: Utah Independent Redistricting Commission)

He told the commission he was aware that the current congressional districts are divided so that all four districts have at least some urban and some rural parishes; In fact, he said he heard feedback from a rural Utah resident who preferred it. He fears, however, that some districts are already determined by urban participation and that all four districts will be at some point if the population continues to develop as it has before.

Unlike Hepworth, Friend also believes cities should be held together as much as possible. Because of this, its Utah legislative districts – a map that was not accepted due to issues with some of the borderline population sizes – kept places like Eagle Mountain and Riverton in the same districts of the House of Representatives and combined Cedar City and Enoch together.

Travis DeJong, a Utah resident and Draper City employee, shared his cards using a similar approach. He said his goal was to keep counties and cities intact as much as possible. Both he and Friend also tried to divide larger cities by neighborhood lines instead of putting the lines across them.

Another approach was to take the current boundaries and adapt them to new populations, which Kevin Jones did. Still, the Utah resident was ready to crown Hepworth the “World’s Best House Card” champion.

The Utah Independent Redistricting Commission has until November 1 to finalize cards that will be sent to the legislature. Gordon Haight, the commission’s executive director, said they had entered “bang time” in their process.

The Utah Legislative Redistricting Committee, made up of Utah lawmakers, is also taking public feedback before recommending potential voting cards for the next decade. Despite the long delays in receiving the 2020 census data, which will be used to identify voting cards, the state is still on track to complete the process before the end of the year.

It is possible that one of the designs released on Tuesday could be selected by the commission before the end of October, when the commission finalizes public comment and submits a draft to leaders. It could also be the state’s last voting card.

Even when it doesn’t, Rex Facer, chairman of the Utah Independent Redistricting Commission, told residents who shared their cards that he recognizes their efforts.

“It is very helpful to see alternative visions of how we can group things together,” he said.

In the meantime, the Commission has also voted to add and change some of its already ongoing public feedback tour. According to the staff, a new event was added in Mexican Hat, San Juan County, on September 29th at the request of the Navajo Nation. A rescheduled meeting will also be held in Moab on October 13th.

The commission has also moved its October 9 meeting from Saratoga Springs to Eagle Mountain and postponed its Herriman meeting from October 22nd to October 21st. The commission has 10 public feedback events planned across the state through October 23.

Facer said Tuesday that the commission will continue to accept public feedback and card designs through October 23rd. All of this can be done through the Commission’s website.

×

Comments are closed.